Confessions Of A Former, Recovering Free-Range Mom

I had forgotten a very important element of parenting: balance.

Tatiana Gordievskaia / Shutterstock

Tatiana Gordievskaia / Shutterstock I got one of those school emails again last week. My child was acting out — knocking over block towers her classmates had built and jumped on top of girls who did not want to be tackled. Could I talk with my child, the teacher asked, about being kind to peers and respecting adults?

I would have expected this email about my 7-year-old son. We have had fairly close relationships with each of his teachers since pre-K, and not because we are overly social or especially generous in our volunteer efforts. No, these relationships have been born of concern and a need to talk about how best to manage his behavior.

These meetings run like think tank sessions or summit meetings to push for a climate of change.

But this email was about my daughter, the 4-year-old.

I can't say I was totally surprised. Still, I had always counted on my daughter being the easy one, social and pleasant, sailing through childhood, graceful and content. I figured the universe owed me one easy kid, at least.

You might say that in hoping for a better fate, I blinded myself to the hand I was actually dealt.

I scheduled a meeting with the teacher and lead administrator, and then went home to do what any good mother would do. I poured myself a big glass of wine after the kids went to bed and wondered what the hell I had done wrong.

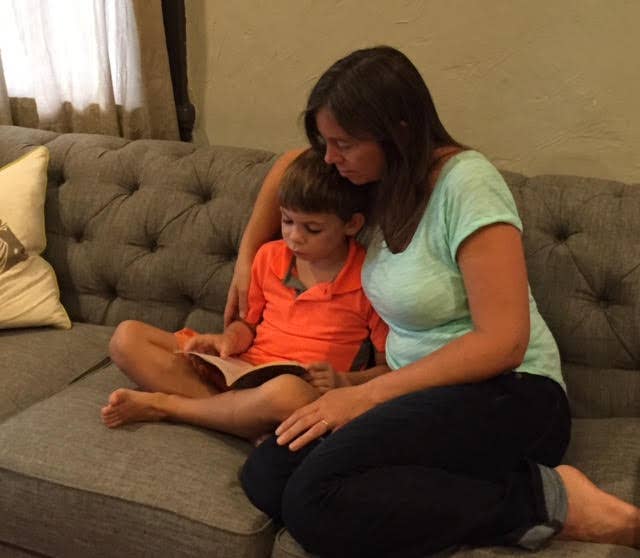

Photo: Author

My mind immediately tracked back to an incident that occurred earlier in the year. I had invited my son's new friend to our house, and his mother had dropped him off, confident and unsuspecting. In fact, the boys played incredibly well for a couple of hours, and I had just texted the mother to let her know that things were going smoothly.

I must have jinxed the play date. I looked over at the three of them. My daughter had put her arms around the friend's waist and was beginning to jump up and down. I looked at her quizzically but said nothing. She responded by squealing and jumping higher, at which point she pulled the friend back, hard.

They fell, and he landed on top of her, his head falling squarely on the bridge of her nose. Two streams of blood opened up immediately, along with her wailing.

When she hadn't calmed down in ten minutes, I called the pediatrician. When she started complaining about being sleepy, I texted the mother. "On the way to the ER," I typed. "Can you meet us there?" She graciously took my son with her back to her house while the doctors checked out my daughter. Luckily, nothing was broken, and they doubted she had a concussion.

But this wasn't the way I wanted to start off a relationship with a new family. The moment felt like another in a long list of embarrassing moments I had suffered as a result of my children's chaos.

I spent the next several times I saw my friend alternating between feelings of shame and forced optimism. She never mentioned the ER visit to me, but I couldn't help feeling as though it was still on her mind. It certainly must have colored her perception of us.

What was there to learn from that incident, I wondered, other than that my daughter's rambunctious play wasn't a new development? What did the moment reveal to me about myself? About my bad choices or failure to intervene? Was I just a crappy mom? Was I the reason my children have always been so out of control?

\When my children were infants, I was a huge fan of attachment parenting. I co-slept. I stockpiled various wraps and slings for baby-wearing. I made my own baby food. I nursed on demand and cloth-diapered. And then something else happened: I grew very, very tired.

Around this time, I also stumbled upon a novel philosophy that seemed out of sync in some ways with the attachment lifestyle: free-range parenting. Where attachment parenting promoted intimacy, free-range parenting advocated for distance.

Yet both philosophies were aiming toward similar goals: raising confident children in tune with their needs. Both methods promised optimal conditions for leading children to develop self-sufficiency and creative independence. To a tired parent who still harbored some nostalgia for her own 1980s childhood, free-range parenting looked pretty attractive.

In the course of a few months, my parenting style did a 180. Whereas I had come home in the afternoons to pour over stacks of books with my children, I began opening the front door instead. I encouraged them to run down to the neighbor's house without me. I loosened my leash.

In the park, I backed off the play structure and sat on the bench. I looked at my iPhone and told them to pump their legs if they wanted to swing. On play dates, I let my son rough house with other boys. I did not step in unless someone looked angry or hurt, and I let extended hours of unsupervised play unravel in my living room.

I did not step in. I did not guide anyone. I simply let them explore their own boundaries.

Photo: Author

No one got hurt. No one seemed short-changed, at least not at the time. But the problem was that free-range parenting was all I did. I had stopped teaching my children, convinced that they would learn life's best lessons through discovery or natural consequences. I had jumped into the deep end of the philosophy, and whoa, was I swimming.

When I met with the teacher and early childhood director the next day, they had a different message for me, one far more aligned with the attachment parenting methods that had defined my daughter's infancy: invest time in your child.

Spend one-on-one time with her, they advised. Let her snap the ends of the asparagus when you cook. Take her to the grocery store, just the two of you, and a make point of being present with her at that moment — no iPhone, for her or for you. Talk with her about her interests. Make connectedness a central part of your experiences together. Doing so will prove to her that she is good.

That's when I realized that I had gotten it all wrong. Somewhere, in the midst of wanting to cultivate my daughter's spirit by giving it free rein to dance about the house and neighborhood, I had forgotten a very important element of parenting: balance.

Sure, freedom can be delicious, and children do deserve long hours to craft their play and narratives. But they need guidance, too. They need it deeply. Otherwise, they lose the sense of boundary they need to be good citizens.

That weekend, I set time aside to play princess with my daughter and to watch her, really watch her, climbing on the dome in our backyard. I joined her narrative. I asked her questions, and I answered hers. She opened up. She was amazing.

As I watched her tightrope walk her way along a cement curb, I realized that the moment was a perfect snapshot of her actual needs: a dance between attachment and freedom, between careful attunement and free play.

Tracey Watts is a writing instructor and mom living in New Orleans.