5 Devastating Truths Religious Gays Wish Our Communities Knew

We're in a lot of pain.

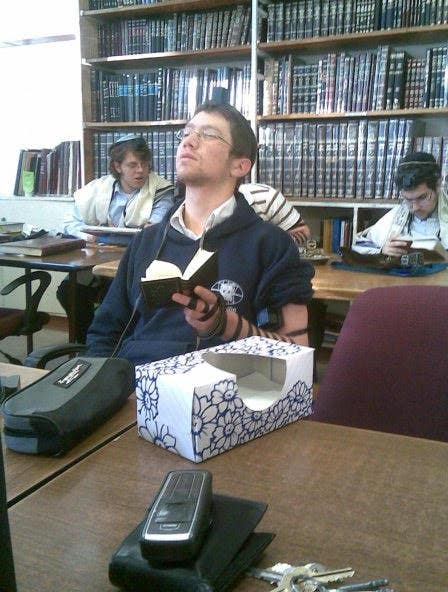

courtesy of the author

courtesy of the author To my religious community: this is what I want from you. "The gay agenda" is a term invented by right-wing Christian groups, but it reflects how communities of ALL faiths see gay activism. It is seen as an attack on morality. An attempt to recruit new members and the normalizing of a perverted way of life.

As someone who actively chose to be religious when I was young — I was raised as an Orthodox Jew — I once held similar attitudes. And so I know and understand a painful truth: I know that many Orthodox religious groups will not change their views on homosexuality. Even those who wish they could are prohibited by what they believe to be God's word. To the religious, gay activism can, therefore, seem like an attack, an attempt to force them to accept something they simply are not allowed to.

But even if unconditional acceptance is unrealistic, there is something we can demand from religious communities. My "gay agenda" is to make them know our pain, and understand and acknowledge the following facts.

1. There are more LGBT Christians, Muslims, and Jews than you think.

There's no clear data as to how much of the general population is LGBT. But I know it's more than religious communities assume.

While I was still religious, I would not have dared to admit to being gay — even in an anonymous survey. I also believed I was the only one in my community. I now know a few dozen "out" Orthodox Jews who used to be (or still are) religious. I know a few who are still in the closet. And no, I have not made a particular effort to seek these people out.

But whether LGBT people number 1 percent of the population or 10 percent, there is a reason to take notice.

2. We're in a lot of pain.

How can I attempt to describe the pain of being closeted? I tortured myself with self-loathing. Shame and guilt accompanied every erection. And the overwhelming terror of being found out never went away.

The main character in 2016's Other People describes the dreadful certainty that his parents would find his magazine cutouts of half-naked men. So, instead of just throwing them away, he cut them into little pieces, soaked the pieces in water, and split them up, before disposing of them in separate trash cans.

It might sound ridiculous to you, but any closeted person can relate. The slightest possibility that someone will piece together the evidence can keep you up, night after night. Did I let something slip while I was drunk? Am I walking like a straight guy? Does my friend remember the time I almost leaned in to kiss him before I caught myself, horrified?

3. We often have no one to talk to.

When I was 19, I fell in love with a friend in Israel. When I left without ever telling him how I felt, I descended into months of depression. The grief of unrequited love, combined with the guilt I felt for loving him in the first place, was brutal.

I made desperate and unrealistic plans to go back, to find a way to be with him whether he wanted me or not. At the same time, I believed there was something inherently wrong with me and hated myself for not being stronger.

During this time, there was not a single person I could talk to. I could not imagine that my family, rabbis, or friends would accept me if I told them the truth. This added a whole new level of pain. I had no healthy outlet for my feelings. I truly believed I had no choice but to suffer in silence. It's no wonder that the experience of being closeted is documented as leading to mental health disorders, including major depression.

Depression is not the same as sadness. That's a discussion for another day. For now, it's crucial to understand that depression often leads to self-harm and suicide (This is the case before so-called conversion therapy. Conversion therapy, proven to be ineffective, on the contrary increases the risk of suicide). We cannot afford to ignore those suffering alone.

4. Many of us are in unhappy, heterosexual marriages.

Of course, many closeted people get married. Marriage is an indispensable element of a religious life. I planned on getting married to a woman, even if I felt no attraction to her. I assumed I'd have to grin and bear it.

Those who do get married might end up divorced. Many, however, choose to stay in an unhappy relationship, with little to no sex life. Still, others search for alternative ways out.

There are a number of frum (ultra-religious) couples in my community who have open relationships. The LGBT spouse is too scared to come out to anyone but his or her partner, and they stay in the marriage to keep up appearances. But both partners sleep with other people.

None of these are solutions. They're hell for both parties. They're hell for any children they have. No one wants this.

5. The gay agenda: to bare our wounds.

I don't have any plans to overhaul a religion. I don't have the desire to convert people to atheism, to undermine their beliefs, or to somehow recruit them to homosexuality. My agenda is to expose the pain that I and millions of others have gone through. My agenda is to shine a light on our gaping wounds, caused by shame, guilt, self-loathing, and overwhelming terror. To show how we continue to bleed because we have no one to talk to.

If there is a gay agenda, it is to bare our scars for our religious families, friends, and communities to see. To give them no choice but to accept that we're not choosing to be gay to hurt others or to bring religious morality to decay.

We're not deviants, looking for perverted thrills. But we are human beings who have been damaged by our treatment at the unwitting hands of those who love us. We are sensitive souls who have faced unbearable rejection for something we wished we could control.

Our goal is not to change religions. We know that we can't alter what was written in the Torah, Bible, or Quran, whether by God or by man. We simply beg those religious communities see us with compassion instead of hatred and suspicion.

We want our collective experience to speak for itself, and for those who claim to care to stop and listen.