Why Fewer People Are Officially 'Coming Out' As LGBTQIA+

Are coming out stories a thing of the past?

the author

the author I’m a 29-year old cis-gender woman and I identify as queer. I’m attracted to women and non-binary individuals; my partner is non-binary.

Easy enough to understand, right?

Unfortunately, it took me a long time to string those words together and find my own LGBTQIA — lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, and asexual or allied — sexual orientation and identity.

I only dated men throughout my teens and 20s, and I had unsatisfying sex for more than a decade.

I frequently fantasized about women; once, I even Googled, “Am I gay?”.

Still, I struggled with internalized homophobia that kept me closeted for far too long.

Finally, after years of wondering if I’d ever find a truly satisfying relationship, I came out as queer at the age of 27.

I say I "came out", but I didn’t really.

When I started browsing OkCupid and going on a few dates, I didn’t sit down with all of my friends and have a heart-to-heart.

Instead, I simply announced, “Yeah, I’m dating someone, and she happens to be a woman.”

The only real “coming out” I did was to my parents, but even then, they were completely supportive and totally unsurprised.

It turns out, there are more women in queer relationships these days who don't feel the need to "officially" come out, and there are multiple explanations for this.

First, I want to acknowledge the fact that the ability to come out without consequences is clearly a privilege.

I am a white, able-bodied, cis-gender woman with an accepting family. I live in a liberal city that embraces LGBTQ individuals. And I don’t live with a daily fear of being assaulted for my sexual or gender identities.

I wish with all of my queer being that everyone could be so lovingly embraced, and I hope that someday they will be.

Countless individuals, particularly trans women of color, face violence, bias and discrimination daily.

Still, the number of people identifying as LGTBQ is on the rise.

In 2017, 4.5 percent of American adults identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, which was up from 4.1 percent in 2016 and 3.5 percent in 2012, according to a Gallup poll from 2018. Furthermore, 5.1 percent of women in 2017 identified as LGBT, compared with 3.9 percent of men.

So, what’s changing?

Generally speaking, society is more accepting, says Dr. Justin R. Garcia, Research Director at the Kinsey Institute.

“Researchers have proposed different explanations for this observed pattern,” Garcia says. “One possibility is simply that with more acceptance and less stigma associated with being a sexual and gender minority, more LGBTQ people are able to ‘come out’ and not hide their identities or preferences.”

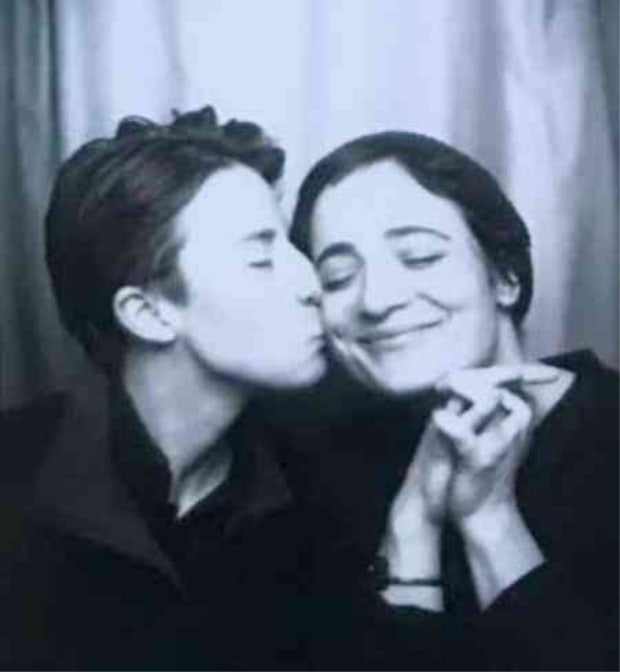

photo courtesy of the author

photo courtesy of the author

While we’re witnessing a rise in people identifying as LGBTQ, it seems that fewer people are feeling the need to come out formally.

As one Vice Sweden article shows, many people's "coming out" stories don't actually involve a formal coming out to the world.

Madeline*, age 23, explains, "Understanding my own sexuality has been a long process. About three years ago, I told my closest friends that I was attracted to girls as well, but I added that I was still confused about where exactly I fit on the spectrum. For me, that didn’t really count as coming out because I couldn’t say for sure how I felt."

Once she was in a serious relationship with a woman, she felt the need to come out formally only to her father.

"That’s probably the only time I came out officially to anyone," she shares. "I tell new people I meet, but in passing — though I’m always prepared to answer a bunch of follow-up questions."

With LGBTQ visibility at an apex, identifying as straight is still considered the norm.

As the poet Adrienne Rich so eloquently stated in an essay titled "Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence": “Lesbian existence comprises both the breaking of a taboo and the rejection of a compulsory way of life.”

The majority of the human population identifies as heterosexual, or at least engages in heterosexual romantic and sexual behaviors, including sexual reproduction.

“I don’t anticipate that will change anytime soon, in humans or other sexually reproducing species," Garcia explains.

“But," he continues, "that doesn’t mean that heterosexuality will or should always be the de facto assumption and norm. In fact, with more accepting attitudes and exposure to various sexualities, we may start to see less people ‘coming out’ as a social event acknowledging a particular romantic or sexual orientation.”

This is exactly what Marie* experienced.

The 39-year-old had only dated men throughout her life, yet experienced emotions for women she later identified as crushes.

Once in her 30s, Marie slept with a woman for the first time and dated her for more than a year. Still, she didn’t feel the need to make a formal announcement to her friends and family.

“I started telling my friends and family after we'd been dating for about a month,” she said. “It wasn't a big, ‘I'm gay’ coming out moment. I've never even called myself a lesbian. I don't really feel like a traditional label. It was more just explaining that I was in a relationship for the first time in a really long time and it was with a woman.”

“We might be able to imagine a near future where people are just attracted to and partnering with others regardless of their gender identities, and rather than see this as atypical, people will accept this as the reality of human diversity,” Garcia says.

If this is the case, the entire notion of "coming out" may just go extinct. And that's probably a good thing.

Until we reach that point, however, there can be a downside to not coming out.

While we’re slowly moving away from the notion of compulsory heterosexuality, we still have a long way to go in terms of LGBTQ rights and equality.

In one of my favorite quotes, the late Harvey Milk implores people to come out for a greater cause:

“Gay brothers and sisters, you must come out. Come out to your parents. I know that it is hard and will hurt them, but think about how they will hurt you in the voting booth! Come out to your relatives. Come out to your friends, if indeed they are your friends. Come out to your neighbors, to your fellow workers, to the people who work where you eat and shop. Come out only to the people you know, and who know you, not to anyone else.

"But once and for all, break down the myths. Destroy the lies and distortions. For your sake. For their sake.”

When deciding whether or not to formally come out, there are two truths: We shouldn’t have to come out, as this demonstrates the fact that we live in a cis-heteronormative culture. And, at the same time, the more people do come out, the more those who haven't done so yet will feel comfortable doing so.

Ultimately, I want people to come out because they feel like it’s right for them; not because they owe anyone an explanation — particularly when it comes to the sacred act of loving someone.

As for my personal story, when I realized it was time to proverbially bat for the other team, I didn’t have to announce it on the cover of Time Magazine the way Ellen DeGeneres did in 1997 — or even via a Facebook post.

Brave people, like DeGeneres, paved the way for me to simply decide one day to switch my OkCupid account to, “Interested in women.”

Still, I choose to come out every day by posting photos of my partner and myself on Instagram and holding their hand in public.

I may not be shouting my sexual identity at the top of my lungs, but I love my partner publicly and unapologetically, and I will never take that for granted.

Unfortunately, Suzette Mullen, 58, didn’t really have a choice about whether or not she could come out.

Her journey is an example of how different the LGBTQ experience was for people in previous generations.

In her mid-50s, Mullen had a deeply established life, including a 30-year marriage and two children. She came out to herself at age 55, and, as a personal writing coach who founded Your Story Finder to help young people share their own unique stories, is currently writing a memoir about her experience.

She attributes her delay in coming out to the previous lack of LGBTQ visibility.

“I knew no one who was gay when I was growing up,” Mullen says. “The only lesbians I had any exposure to were very butch, and I didn’t identify that way.”

It was hard for her to see herself as fitting in the LGBTQ spectrum, so she didn't know where she belonged.

These days, young women have as many examples of queerness as they can imagine, so perhaps understanding themselves is easier.

Maybe we can someday get to the point where people don’t even need to come out — even those who have been in heterosexual relationships for decades.

If someone has identified as straight for their entire lives finds themselves attracted to the same sex, it doesn’t have to be viewed as radical if they identify as LGBTQ later in life.

In fact, an increasing number of women don't necessarily identify with a particular label, instead taking on a “sexually fluid” approach, particularly once they’ve hit their 30s.

In an article published by InStyle, the author, who had her first queer relationship later in life, discovered that her experience wasn't all that uncommon.

"My whole life, I dated and loved only men. But when I told family and friends I was dating a woman, no one seemed shocked — for some reason, that bothered me ... Though I was raised by a free-spirited nomadic mother in a liberal environment surrounded by queer folks, I felt compelled to make it clear that I wasn’t coming out. This was situational. I had simply fallen in love with a person and that person happened to be a woman ...

"During downtime at work, I started searching for an explanation. What I found was a surprising amount of research. Every doctor I subsequently spoke to had slightly different theories on the matter, but all of them agreed on one thing: late in life sexual fluidity in women actually isn’t all that uncommon."

When I asked Mullen whether or not she would have come out sooner if she grew up in this era, she responded with an emphatic, “Absolutely!”

“I think I would have had role models to put into words the feelings I was having as a teenager and then later as a woman in her 30s and more,” Mullen says. “For the first time, I feel like me. That undercurrent of discontent and restlessness that plagued me for most of my marriage is gone. I felt like there was something wrong with me that I couldn’t be happier with all I had. Now I understand why I wasn’t.”

My hope is that everyone can find happiness on the other side, regardless of whether they formally come out.

Not living as your true self is a particular form of hell, and until everyone can embrace their sexual and gender identities without consequence, there is still work that needs to be done.

*some names changes for privacy

Bonnie Horgos is a freelance writer based in Minneapolis, who writes about feminism, LGBTQ issues, gender-based violence, health, and wellness. For more, visit her website or follow her on Twitter.