No, Being Raped Doesn't 'Ruin' Your Life — And Here's How We Should Talk About It Instead

The language we use around rape victims matters.

Jose AS Reyes / Shutterstock

Jose AS Reyes / Shutterstock “He ruined her life.”

Every time I hear someone say that about a woman being raped — and I hear it all the time — I want to scream.

It always jabs me. I was raped. Does that mean I am ruined?

I know that it’s an earnest attempt to make clear the heinousness of the crime, which is justified. It’s our collective rage speaking. It’s what happens when unbridled anguish gets smooshed into an inadequate vocabulary.

But there has to be a better way to convey the trauma and horror of the experience of being raped or sexually assaulted than by saying a rapist "ruins" the life of the person they chose to harm.

Think about it — saying, “He ruined her life” puts a life sentence on the victim, not the rapist.

It’s hyperbolic language meant to make a strong point in the steadfast grip of both rape culture and purity culture, but our rage and any sense shame should be on the rapist, not the victim.

For the victim and rape survivor, we need to offer hope and healing. Not a shame-filled, ultimately victim-blaming life sentence.

I was raped 33 years ago.

A stranger broke into my home, held a gun to my head and raped me in my own bed.

I can’t tell you how often it crosses my mind now, but it’s not often. When it does, there’s something analytical in the details seen through a retrospective haze. It’s a thing I talk about easily these days, with less emotion than when I discuss my divorce.

Granted, it wasn’t always like this.

In the immediate aftermath, I had frequent panic attacks — the kind that landed me in the ER once, sure that I was having a heart attack. Even after I knew what they were, they just left me crumbled in the corner of public restrooms, sweating, so that passersby were the ones thinking I was having a heart attack.

After that stage, there was a sort of numbness that eventually gave way to a low-grade fear that followed me like an ominous odor; I literally wondered if other people were aware of it coming off of me.

Eventually, it was just gone.

Some say this type of reaction is typical of Rape Trauma Syndrome (RTS), a theory developed by psychiatrist Ann Wolbert Burgess and sociologist Lynda Lytle Holstrom, meant to describe and classify the symptoms of psychological trauma experienced by many rape survivors during and after the attack.

Although it's not an official diagnosis, RTS is defined by Wikipedia as, "[A] cluster of psychological and physical signs, symptoms and reactions common to most rape victims immediately following a rape, but which can also occur for months or years afterwards."

Like most survivors of trauma, I still have some PTSD.

The flashes come out of nowhere, but they are years apart, and with the help of therapy and other forms of healing, I’ve developed a skill set that works for me to tame them into the background.

I feel very lucky. I have a life of peace, love, and great relationships. A life overflowing with fulfilling sex, thanks to a partner who understands who I am, and what I’ve been through.

This is my hope for everyone. Not just to survive, but to deal with shame enough to finally shed it, and have hope that you can have sex after rape — even great sex.

I got lucky, in a lot of ways. I have friends and family that I could count on to support me no matter what.

I was also society’s "ideal victim": There was no way that I, or anyone else, could spend even a moment suggesting that my rape was my fault.

Don’t get me wrong, I was asked all the insulting questions, including “what were you wearing.”

But the retort of “I was sound asleep in my bed, he broke in and held a gun to my head,” shuts people up pretty quickly.

It is absolute BS that those things should even matter. No victim is ever to blame. But I was able to escape society’s questioning, which is a thing that continues to hurt victims, long after the initial assault is over.

When someone is raped, we question them. Where they were, who they were with, what they were wearing. As if those very things, the victim themselves, are to blame for their attack.

They are not. And they are not to blame if they didn’t “fight back” or report the crime immediately.

The only person responsible for rape is the rapist.

When Elizabeth Smart was found after having been abducted and raped for 9 months, people asked her why she didn’t try harder to escape.

Setting aside how hideously wrong and victim-blaming that question is, her answer stuck with me. It’s a perfect illustration of how using purity culture to conflate sex with rape harms victims even further.

During a speech at Johns Hopkins University (which you can watch, below), Smart said:

“I was raised in a very religious household that taught that sex was something special that only happened between a husband and a wife who loved each other, and that's the way I had been raised and that's what I had been determined to follow — that when I got married, then and only then would I engage in sex. And so after that first rape I felt crushed, I felt so dirty and so filthy. I understand so easily why someone wouldn't run because of that alone."

Smart’s religious upbringing taught her that sex outside of marriage ruined her, but it didn’t teach her the difference between rape and sex.

In her mind, what happened to her was sex. Hopefully, we can all see now that it wasn’t.

Sex is something consensual between adults. What happened to Elizabeth Smart was rape. That distinction matters greatly because sex is a choice that all parties make together.

Without consent, it’s rape — no matter what.

Smart has often told the tale of a teacher who compared sexuality to gum.

“Imagine you're a stick of gum and when you engage in sex, that's like being chewed,” the teacher would say. “And then if you do that lots of times, you're going to become an old piece of gum, and who's going to want you after that?”

So she believed she was ruined. That her whole life was ruined.

Everything about her case was extreme, but the principles still apply to how we talk about rape in general.

We tell survivors that they’ve been ruined, which is a kind of shame that’s hard to overcome. It’s also a shame that may just lead to silence, which lets the rapist off the hook, and leaves the survivor carrying that weight alone.

Why do so few victims ever report?

Maybe because we blame them for their own rapes. Maybe because we tell them their lives are ruined.

So what’s the point then? Where’s the hope?

According to RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network), every 98 seconds an American is sexually assaulted, and 1 in 6 women and 1 in 33 men have been victims of attempted or completed rape in their lifetime.

When we start talking about all forms of sexual violence, those numbers skyrocket.

For instance, 1in6.org reports that at least 1 in 6 men have been sexually abused or assaulted. Most people believe all of these numbers are underreported, for obvious reasons.

Either way, that’s a whole lot of people, and it’s reasonable to assume many of them have been able to recover from having been raped, and that they are living full and happy lives.

That’s not to say it was easy to get there, or that everyone’s process was the same in any way, just that there’s hope.

And that's a message I know, very personally, that survivors of rape and sexual assault need to hear.

I know that, for me, recovering from rape took time and support, but it did happen.

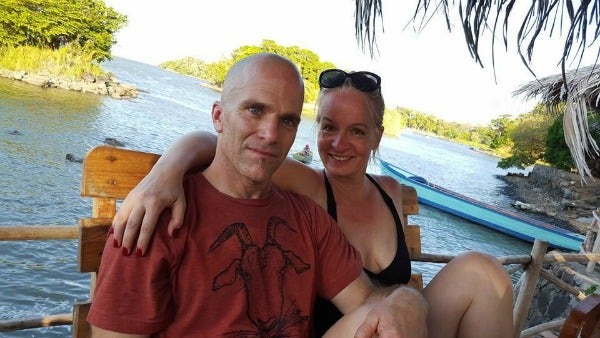

Photo courtesy of the author

Photo courtesy of the author

So, what is the best way for people to recover from rape or sexual violence?

For answers, I turned to two mental health professionals who help survivors heal and move on from rape trauma.

Jennie Bedsworth is a clinical social worker in Columbia, Missouri, whose practice focuses on helping people recover from trauma and live the lives they want to lead. After speaking with her, I feel that my experience in that early stage of recovery was typical.

She explained to me that, "[I]mmediately after a rape or other assault, it’s normal to experience PTSD-like symptoms. This is the mind/body in shock, adjusting to what happened. At this time I encourage people to do whatever they need to do to feel better. At the same time, allowing yourself to have natural emotions, process, and slowly get out into life again (that last one may take a little more time) can be very helpful.”

She also suggests that reaching out to your existing support system, rather than isolating yourself, can be helpful.

However, that part can be hard for many survivors. I know that my incredibly supportive family and friends made all the difference, but I realize not everyone has that.

“Beware of friends who tell you to ‘put it in the past’ or something similar, or who just change the subject,” she clarifies. “If at any point someone you talk to is not affirming (even if it’s a professional), or can’t accept your feelings, or makes you blame yourself, consider getting out of that situation and keep looking until you find a supportive person or group.”

If you don’t have a support network that you feel safe talking to, you can contact the RAINN National Sexual Assault Hotline and they will connect you with a support group near you.

Just call 800.656.HOPE (4673) to be connected with a trained staff member who will help you through.

What about returning to the kinds of situations that might be triggering?

For many survivors of sexual assault, the people, places, and things that trigger memories and flashbacks aren't easy to avoid long-term. Bedsworth encourages baby steps into those places.

“If you know a place is generally safe, take small steps like going for a short visit, or going with a friend,” she says. “If you lean in gently, rather than avoiding, you will gradually get your confidence back and start to feel better.”

One of the things that seemed impossible to me was the idea that I would ever want to have sex again after being raped.

Specifically, because I was raped face-down and never saw my rapist, I was afraid that I would never ever be able to have sex in that position.

I was very wrong.

Don't get me wrong — it took work. As Jennie Bedsworth advises, I had to take it very slowly. We’re talking years before I returned to that position. And I had to tell my partners about it, essentially warning them that I may get triggered.

For me, the sheer act of that communication made me feel safer.

Expressing both my truth and my boundaries to my partners became not only a vetting tool for people I would feel safe having sex with, but also a tool in my own recovery. It was a process of learning to trust both myself and my partners.

Next I spoke with Stefanie Goerlich, LMSW, a counselor who specializes in sexual relationships and survivors of sexual trauma.

“If there are people around you who consistently fail to respect your limits," she explains, "who minimize your voice or experiences, or who push your boundaries, don't feel obligated to extend third, fourth or fifth chances to improve. Likewise, when we express our needs and our expectations and the folks around us rise to the occasion? Allow yourself the luxury of extending trust. The people who consistently respect your needs are people worthy of your trust.”

In a world that seems to prioritize being “nice,” and not making anyone uncomfortable, it can be really hard to speak the truth about what you’ve been through, and what you need as a result.

It took me years of practice, but it’s a lesson I’ve tried to pass on to so many people, in so many contexts.

You do not owe anyone your time or your body. You get to decide who you let in — figuratively and literally.

“If someone is behaving in a way that you find uncomfortable or disrespectful, give yourself permission to speak to that," Goerlich explains. “One of the best ways to learn to set boundaries in high-tension situations is to practice doing so when the stakes are low. Asking for what you need, whether that request is ‘I need you to put your dishes in the sink’ or ‘I need a few minutes alone right now’ helps to build the emotional muscle-memory that enables us to say ‘I need you to leave, right now’ when the stakes start to feel higher.”

As simple as that may seem, that literally lays the foundation for a life filled with safe, joyful and intimate relationships.

“There is no timeline. No recipe for healing. No magic formula for recovery,” Georlich explained to me. “Be gentle with yourself. Allow yourself space to feel and time to grieve. Your journey may look quite different than mine, but you are already a survivor and that in and of itself is something to celebrate.”

33 years after my own rape, that still rings true. And it still feels soft and soothing when those words land in my soul.

So many of us have been through this, in so many ways. And so many of us have taken such a wide variety of paths to get where we are today. There’s no right or wrong way to heal.

There’s no universal truth, except that it’s not your fault. And you deserve to be happy.

Find help if you feel you need it.

There is hope.

Alyssa Royse is a writer and speaker who likes to take on social justice topics related to bodies and sexuality. When she’s not writing, she’s usually in the gym that she owns with her husband, either working out or training youth weightlifters.